Frederick Sommer

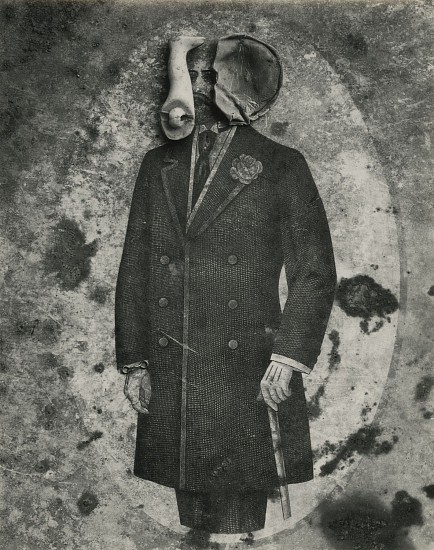

Frederick Sommer, Prince Albert, 1947

Vintage gelatin print; printed no later than 1949, 9 1/2 x 7 9/16 in. (24.1 x 19.2 cm)

Mounted; signed, titled "Photograph" and dated in pencil on mount verso.

8531

Price Upon Request

Provenance: Sommer to Dieter Weiss, 1949.

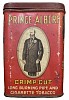

Frederick Sommer was drawn to Surrealism. However, like other artists of the time, he wasn’t interested in their devotion to unleashing the subconscious to explore the metaphysical. Sommer’s Prince Albert utilizes a found object, a tin of Prince Albert tobacco, on which he has placed several objects including the leg of a doll or toy. The image of Prince Albert, soon to be King Edward VII (1901-1910) of the United Kingdom, namesake of the Edwardian era, is transformed to look as if he has the head of an elephant.

Apparently, on May 21, 1887, Alexandra of Denmark (1844-1925) the Princess of Wales, Prince Albert’s wife, visited Joseph Merrick, known as the Elephant Man, at London Hospital, where he lived. “Princess Alexandra shook Merrick's hand and sat with him, an experience that left him overjoyed. She gave him a signed photograph of herself, which became a prized possession, and she sent him a Christmas card each year.” [see Wikipedia]

I am unaware of Sommer’s full intentions for this work or even if he attended to use the image from one of the most popular American tobacco brands of the time to allude to the Elephant Man, let alone the kindness of the Princess of Wales. Yet, by photographing the assemblage of objects on the image of Prince Albert, and the distressed surface of the tin, Sommer equalizes each element to the same dimension. The photograph depicts the detail and reality of the moment while alluding to the time of Prince Albert. Knowing this print was made within two years of the negative, and not reprinted later, adds further immediacy to Sommer’s expression.

Curator and art historian, Ksenya Gurshtein, (then the A.W. Mellon postdoctoral curatorial fellow in the department of photographs, National Gallery of Art, Washington) wrote an exceptional feature on Frederick Sommer for the NGA website. She stated: "Sommer did not expressly identify himself with the surrealist movement, though he exhibited with its members several times. Nevertheless, his work reveals that from the late 1930s he was interested in many of the same themes and approaches that the surrealists had begun to explore in the 1920s. The Sommers first met Max Ernst (1891–1976), a prolific surrealist, in 1941 in Los Angeles after Ernst came to the United States fleeing World War II. The friendship deepened after Ernst and his wife, Dorothea Tanning, came to visit the Sommers in 1943 and moved to Sedona, Arizona in 1946… Sommer met Man Ray (1890–1976) in 1941 at the same party in the Hollywood Hills where he met Max Ernst, and afterward the two men continued to follow each other’s work from afar…"

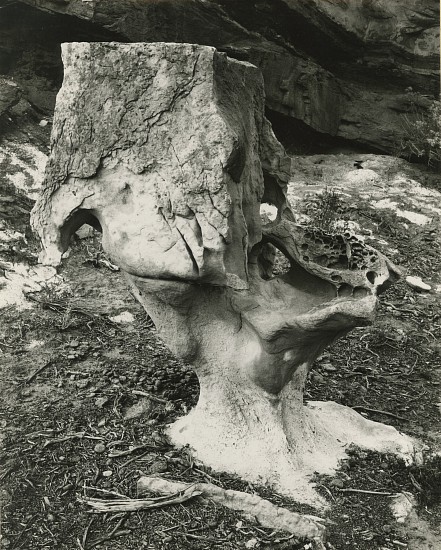

Frederick Sommer, Certitude, 1942

Vintage gelatin print; printed no later than 1949

Mounted; signed, titled "Photograph" and dated in pencil on mount verso.

8530

Price Upon Request