BIOGRAPHY

1921-1997

A masterful technician in the darkroom, Sudre employed and created innovative techniques that amplified the abstract and suggested both spiritual and metaphysical concerns.

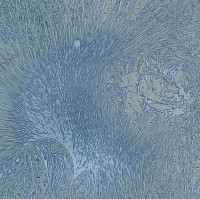

Enamored by the wonders of nature and the possibilities of photography, his investigation began in the early 1950s photographing nature. His work evolved to evoke nature's infinite textures and patterns. In the 1960s, he took his explorations of nature toward the micro, creating crystals on glass plates that he would use as "negatives." Sudre employed the Mordançage technique on many of these prints, which he invented based on a late nineteenth century process known as etch-bleach.

Mordançage solution includes hydrogen peroxide, acetic acid and copper chloride. Once a fully processed gelatin silver print was immersed in the solution, the print became bleached, and the areas with the most silver (the most exposed and thus darkest areas of the image) would swell and lift off the paper base. Sudre would then wipe them away, leaving an outline of the latent image. Next, he would thoroughly wash the print and redevelop it. He used a variety of developers in differing ratios, often making his own photographic chemistry. He was therefore able to achieve a range of colors from the various toners he used and by letting the developer oxidize.

His dynamic and expressive use of color became an integral part of his work. Sudre emphasized the symbolism in his work with his titles and by the 1970s he had begun to combine cliché verre images with photograms and even found illustrations.

Jean-Pierre Sudre was born in Paris in 1921. He studied at l’Ecole Nationale de Photographie et de Cinématographie and at l’Institut des Hautes Études Cinématographiques. Due to the limited opportunities in cinema, Sudre decided to become a professional photographer. Growing up, his family owned a property surrounded by woods; it was there that he became entranced by nature. In addition to his commitment to his own work, Sudre was an influential teacher in both traditional and experimental photography. He created the photographic department at the School of Graphic Art in Paris. In 1974 Sudre and his wife Claudine, a fine photographer and printer in her own right, moved to Lacoste and opened a research center, later named the Association for Professional Training and Research in Photography, where photographers would spend nine months immersed in photography.

During his lifetime Sudre's work was exhibited throughout Europe, including the Musee d'Art Moderne in Paris and the Palais de Beaux Arts in Brussels. He was featured in the Museum of Modern Art's exhibition A European Experiment in 1967 along with Denis Brihat and Pierre Cordier, an exhibition, curated by John Szarkowski, emphasizing color and texture and the physicality of photo-based work. Sudre’s work is represented in international institutional collections, including the Center for Creative Photography, Tucson; Cincinnati Art Museum; Centre Pompidou, Paris; The Gernsheim Collection, University of Texas, Austin; Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris; The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; Musée Nicéphore-Niépce, Chalon-sur-Saône; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Princeton University Art Museum; Saint Louis Art Museum; and the Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

"Sudre’s experimentation, which continued until the early nineteen-nineties (he died in 1997), remained marvelously various, ranging in tone from psychedelic to scientific. It should be mandatory viewing for the new school of young photographers investigating the pleasures of the darkroom."

— Vince Aletti, The New Yorker, March 14, 2016

When I was first approached by Jean-Pierre Sudre's daughter in 2014, I told her Sudre's work was not for me. I had only viewed it in a book, so she persisted and promised me I would have a different reaction once I saw the work in person. After agreeing to meet in Paris during Paris Photo, I had my first opportunity. I remember my heart filling and my eyes watering as I looked up at her after viewing the prints. I have never been so grateful for being wrong. — Tom Gitterman