Recent Press: ALLEN FRAME in ARTFORUM

February 1, 2019 - Matthew Weinstein

ALLEN FRAME: INNAMORATO

curated by LIA GANGITANO

PRATT INSTITUTE Oct—Dec 2018

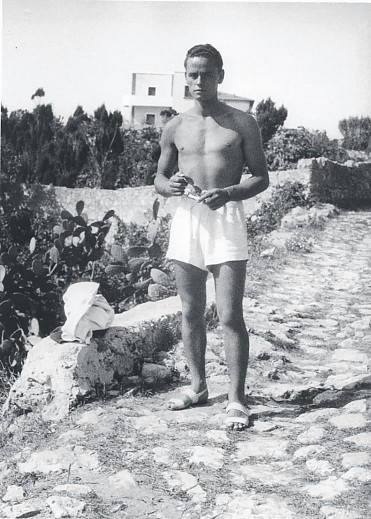

“Innamorato,” an exhibition by the writer, filmmaker, and photographer Allen Frame, was dominated by Ennio, 2018, a room-size installation made up of more than fifty found Italian Mussolini-era photographs of an air force pilot, his sister, and a handsome young man. The pictures, hung salon style, were set into a variety of secondhand frames. The subjects of the photos appeared well off, beautiful, and youthful. They could be seen with skis in the mountains and cavorting on beaches, bringing to mind the bourgeois family in Vittorio De Sica’s 1970 film The Garden of the Finzi-Continis.

Seven photographs of Ennio were printed by Frame from negatives he purchased along with the photos. Every portrait is full body, and in each one the man is ready for pleasure, be it in sun or snow. Is he an object of desire for whomever took the pictures? Is it the handsome friend and his sister who yearn for him? Or is it the artist, who rescued these people from the obscurity of a flea market? Or could it be us? Perhaps it’s all of the above. Included in the installation were hand-written passages in Italian taken from Absalom, Absalom! (1936), William Faulkner’s tale of a sibling love triangle—thus revealing the narrative that Frame projected onto the images.

In the same room as Ennio was a Super 8 film, made by the artist when he was nineteen, capturing his childhood friend Barry. Frame lingers over the soulful-looking and shaggy-headed Barry. It’s difficult to not love Barry a little bit, because Frame’s affection for him is so palpable. The artist, whose best-known photographic work consists of obscured portraits of various acquaintances in intimate states of reflection, was clearly on his way to his mature work.

Photography can run counter to morality, particularly where issues of privacy and ownership are concerned; yet art that violates these boundaries is often the most interesting. By weaving his fantasies into the private lives of these unknown figures, presumably deceased—or inserting himself into the stories of people he wants to be—Frame is not unlike Tom Ripley, Patricia Highsmith’s dangerously charming confidence man.

Queer desire, as it has been represented in art, exists between the polarities of melancholic longing and overfulfillment. One could place Frame alongside Richard Hawkins and Jack Pierson, artists whose work represents a condition in which sexual satisfaction is a warm interior, and they are standing just outside of it, their noses pressed up against the glass.

Curator Massimiliano Gioni’s 2016 exhibition at New York’s New Museum “The Keeper” explored the idea of the artist as collector. Artists such as Henrik Olesen and Hank Willis Thomas, both of whom were in the show, amass and exhibit visual archival material bound up with their own sociopolitical identities. Other artists, similar to Frame, deal with collective memory by exhibiting other people’s family photos: Délio Jasse and Oliver Wasow, who retrieve and sort countless online images, come to mind. A market, along with a certain kind of connoisseurship, has developed for the anonymous photo.

What makes this more sentimental order of appropriation relevant is how it positions itself in relation to the massive collective memory that is the internet, and it doesn’t matter if the image is rooted in a lived moment or not. The impulses to present the image as analogue or digital are beside the point, especially in relation to the broader idea that our memories have never really been entirely our own.

Back to News