Recent Press: Jean-Pierre Sudre in Collector Daily

October 25, 2019 - Loring Knoblauch

One of the consequences of the digital revolution in photography is that we have lost some of the expressiveness that was inherently embedded in chemical processing. Of course, we now have new kinds of “process” remnants to explore – pixelization, software glitching, filters, digital mark making etc. – but these effects are largely different from watery chemicals flowing over paper and leaving behind physical residues. If we want this kind of process uncertainty, we need to go back to approaches that were developed before the workflow transformation took place.

Jean-Pierre Sudre’s photographic abstractions from the 1960s and 1970s are deeply rooted in chemical processing, so much so that their “subject” is the outcomes that result from layered experimentation with complex chemistries. Sudre was deeply interested in the mysteries of nature, and much of his early photography (as seen in a 2016 survey show, reviewed here) looked closely at things like ice crystals, feathers, and spider webs, finding whole worlds of ordered patterns and repetitions in their depths. But by the mid 1960s, Sudre had more fully moved into the darkroom, where he could create his own compositions in situ, via solutions of salt crystals on glass.

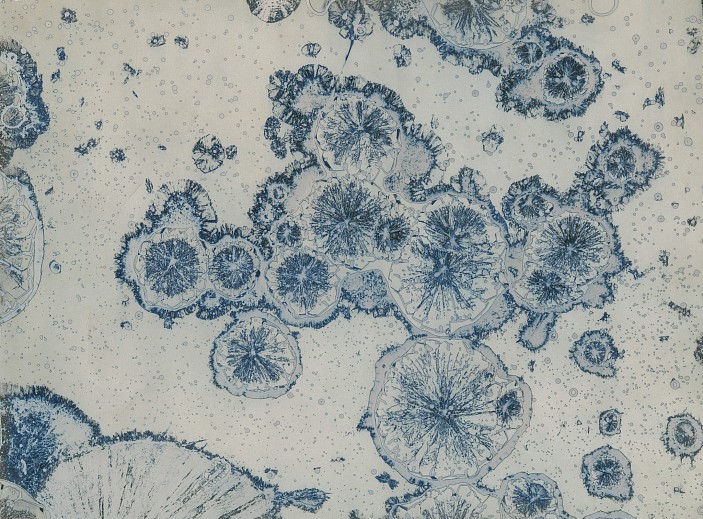

What Sudre was up to process-wise isn’t entirely known, so we can’t track a line of causation that tells us “he did this to get that visual outcome.” What we do know is that the crystal formations on glass were placed on the enlarger and photographed, so the resulting compositions are cropped views and magnified sections of the larger experiments. At their most straightforward, these result in gelatin silver prints, with patterns that recall faceted and dusty crystallized ice; the verticals of ladders, semiconductor circuit boards, or stalactites; gridded city maps with dots of light; jagged repetitions of squares and triangles that unspool into layers of fractals; blocks of floating ice; nested layers of pulled sinews and muscle fibers; or a primal soup of swirled light and dark. They are pictures to get lost in, their abstractions either isolated by type or mixed together in larger compositions that morph and reform within the span of the frame.

Sudre also toned some of the prints or let the developer oxidize, adding color to the images. This gave him an even wider range of expression – a tint of green giving a bubbled swirl a sense of ectoplasm, a soft yellow hue coloring the liquid around the crystallized cubes, and a brown shade giving a squiggled array of spots the feeling of an animal print or sandy tidal flats. A large blue-tinted print is the most impressive of these examples, where intricate networks of lines and tunnels explode into arrays of falling lines like the sheeting rain in Hiroshige’s woodblock prints.

Sudre is likely most famous for his Mordançage process, an approach inspired by the 19th century etch-bleach process. Sudre’s technique started by placing a finished print into the Mordançage solution, which would soften up the areas with the most silver content (the darkest areas). He would then wipe these away, leaving behind the highlights and midtones, which were now etched in a kind of raised relief that is easily seen in raking light. The works on view here that employ this process are richly tactile, the impossibly thin lines of his abstractions now given depth, dimension, and texture. Circular crystals look like round flowers or sliced root vegetables, and a spiraling composition (which Sudre named after the sun) is filled with implied motion, like a circular saw blade with delicate feathery edges.

In the realm of photographic abstraction, Sudre’s pictures stand out – his mix of processes and experimentation led to works that don’t look like anything else we’ve seen before (or since). Their extremes force us beyond simple admiration of their rhythms and complexities into a grasping search for analogies – their strangeness looks like something else, what exactly we can’t quite say. These are intense photographic expressions, ones whose densely packed mysteries and allusions keep us wondering.

Back to News